7 things the Viable Systems Model can tell us about scaling social change

11 minute read

Projects that want to change things for the better tend to fail. They fail a lot.

They don’t fail because they couldn’t help people. Most interventions will do some good and a fair number produce truly spectacular results. But problems arise when the project is opened up to more people, whole communities are opted in, and then suddenly those results start to look a little less spectacular.

It’s still good, don’t get me wrong, but not as good as the pilot. Somehow, making it up as you went along made more of an impact than the polished decision trees, process manuals and protocols you spent months lovingly drawing up.

But this is the beginning of the end. As rollout follows rollout, effect sizes shrink and what was once a shining beacon of hope for a brighter future becomes duller, more tarnished, until you are left with something that is definitely - definitely - better than nothing, but not nearly as good as it was. A future of ‘better than average’ awaits you.

That’s not why we ran this programme, godammit.

If you’re lucky, it will become the new ‘best practice’ some day, even though it’s not at its best.

And don’t worry, someone says. That’s just what happens when you scale. The pilot always produces better results.

Yeah, but, why?

That sucks.

What makes social change fail at scale?

Hello, complexity

We usually think about things growing at a linear rate.

If one chocolate bar costs £1, two chocolate bars costs £2, and the total cost of giving one hundred people a chocolate bar is £100 (which is, of course, very generous of you). This is nice and simple linear growth.

And this is exactly how most people scale their projects. Reaching one hundred people costs £100x so reaching two hundred people costs £200x, etc. Simple maths.

However, when two or more things come together they tend to form some sort of relationship.

This relationship makes things interesting, because now two things together can do more things than two things on their own, i.e. the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

One magnet on it’s own is not very exciting, but two magnets together creates a whole new set of possibilities. Add a few more and you suddenly hold the power of life and death over your household electronics.

These new relationships are known as emergent properties, and these interfere with our assumption of linear growth.

Taking our groundbreaking chocolate intervention as an example, if we want to scale from feeding one person to feeding one hundred we may have to account for any number of new relational properties:

There’s a deal on our chocolate bars and it’s buy one get one half price: feeding one person costs £1 but it’s only £75 to feed 100 people.

The first person to get a bar posts about how great the free chocolate is: there is a stampede to get one and you run out quicker than expected.

Expectations are now so high about the quality of the chocolate that more people are dissatisfied with it when they receive one.

As more people are given chocolate the balance of expectation shifts: now people are not particularly happier when they get one but they are really unhappy if they don’t have it.

You buy more and more of the chocolate: suppliers end the deal and start ramping up prices to account for the higher demand.

I was once involved in a project to investigate how anxiety in autistic children might differ from neurotypical children, which involved taking saliva samples during a test. We would go to schools and talk to children about anxiety while also recruiting for the study, mentioning the saliva sampling. In one school we had no displays of interest at all, which was quite unusual. We later found out one of the children told everyone we were secretly taking DNA to put in a national database and the students were too scared/suspicious to take part.

Fair enough. Really dented our recruitment figures though.

These emerging properties create all sorts of complexity and you won’t be able to predict exactly what will come up. All you can bank on is the more people in your social intervention, the more ways they have of behaving.

This is actually one of the reasons humans are so successful as a species. We are social animals and love getting together because we can do so much more.

The other major survival trait of the human race, and the second reason social change often fails to scale, is diversity.

Diversity comes in many forms - no two sets of beliefs, bodies, biologies, homes, hamlets, personalities or pregnancies are the same. People get ill differently, people get happy differently, people work differently. This is great for the species, as any change will affect some people and not others, known as resilience. It also means large groups of people are more resilient to your intervention than your carefully selected pilot.

The two main sources of diversity we need to concern ourselves with are people-based and place-based.

More people means more values, needs, and access requirements to take into account. A greater territory covered by an intervention means a greater variety of terrain and delivery challenges to factor in.

All in all, more people or larger spaces means more complexity.

Now that we know complexity is both place-based and people-based, and comes from greater diversity and the emergent properties of a system, we can look at how this affects our social change project the minute we scale.

One model to rule them all

Stafford Beer’s Viable Systems Model (VSM) is the perfect model to scale with. It’s based on the observation that systems in the natural environment - from microscopic cells to organs to bodies to whole ecologies - scale very well.

I won’t go into the VSM in detail, although if it piques your interest I thoroughly recommend searching out a few articles on it. The basic premise is that all systems interact with a complex environment and must somehow translate that complexity into something of value in order to survive.

Cells take in surrounding molecules to produce energy, farmers turn weird dirt into valuable food, teachers tailor lesson plans for efficient learning, a charity shop takes unwanted goods and creates a cash flow, etc.

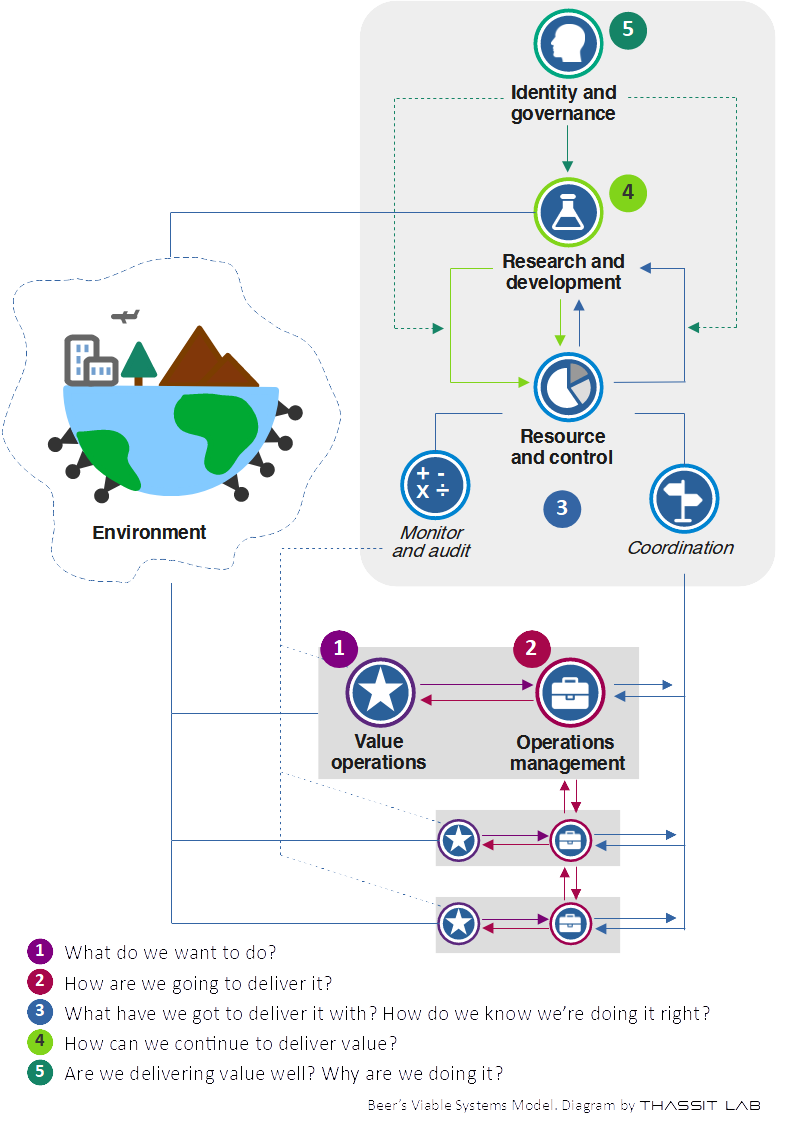

This value is created and managed through five key processes.

Process 1 is everything that creates value directly, such as the distribution of chocolate bars to people. Process 2 manages these operations, such organising chocolate deliveries to the distribution site. There may be many Process 1 and 2 pairs in order to create a given value, such as how the different positions in a football team plus their coach or captain create a match.

Process 3 makes sure these Value and Management operations are properly resourced and are delivering the value they are supposed to. It checks this using audit channels, which feed back into its coordination activities. Process 4 looks at how value can continue to be delivered in the future, given the changing nature of the environment they are working in. Finally Process 5 looks at what value it wants the system to deliver and why.

If any of those processes fail, the system will not survive long.

The key to survival is that the complexity of the environment must be matched or surpassed by the complexity of the system, or ‘only variety can absorb variety’. This is known as Ashby’s Law.

So because our social good projects must deal with more complexity at scale, the project system must also adapt to compensate.

And therefore, rolling out a community intervention that is only as complex as its pilot will always fail to deliver. Simply more, in this case, definitely means less.

Working out which system processes are affected is relatively simple. You will not know exactly what complexity will be thrown at you, but you can prepare to absorb it.

There are two ways to do this:

increase your system variety in turn, e.g. increase worker flexibility

reduce the complexity you deal with, e.g. targeted campaigns

So with that in mind, let’s look at the different processes in the VSM to see how they are impacted by increases in people or place.

Insight 1: Value complexity increases greatly with people but varies with place

We’ve already noted that more people have a greater variety of values, so our value operations must reflect an increasingly complex set of value and access needs the more people are involved.

Similarly, the greater the expanse of territory covered by our intervention means the more challenges there are in getting value into the hands of the people.

How much value-related complexity you have to deal with when increasing your area of operations depends on how different the terrain is. A city tends to have lots of variation (offices, tower blocks, rivers, slums, markets, streets, etc.) whereas digital territory tends to be more homogenous (although you may still have to account for differences in statutory regulations, download speeds, etc.).

Universal Credit is an example of failure to absorb value complexity as a program is rolled out. Initially piloted in groups with relatively simple benefit-related needs (such as single white men living at home without childcare responsibilities), the same system was expanded to include groups such as people with learning disabilities, part-time carers and working families. Each had different requirements, so for instance receiving benefits every month worked well for the early pilot group but didn’t reflect the needs of people who were previously paid weekly or had difficulty managing savings. Pressure to speed up the rollout prevented adequate adjustments, contributing to what is now a brutally painful system that entrenches poverty almost as much as it alleviates it. As an added emergent property, some people now avoid signing up or actively fight against the ongoing rollout.

Insight 2: Operational management complexity increases only as much as your value operations do

If the value you deliver and the way you deliver it is going to become more complex, then so too should your management of those processes. This is option 1 in absorbing complexity.

If however you decide to attenuate the variety instead, such as by reducing everyone’s requirements into one of three packages or dividing a territory into four sectors, your operational complexity need only increase a little.

Insight 3: Resource needs become a little more diverse with people and place

More complex needs and access requirements suggests a greater nuance in your resources and how you distribute them. This doesn’t necessarily mean ‘lots more money’, for instance meeting mental health needs in a large community might need four types of (equally costly) specialist instead of three in order to maintain the same relative level of value.

Again, your terrain will determine how complex the challenge is of getting these resources to where they are needed. As this process refers to moving resources internally (i.e. everything not about delivering value directly) most of the time there will be just a small increase in complexity.

For instance making an online bank transfer from head office won’t alter too much whether you cover three square miles or three hundred (unless one of those miles is in an area with different regulations). But getting water treatment chemicals to remote workers in three miles of rolling countryside and a three hundred mile stretch of canyon is a whole different kettle of poisoned fish.

Insight 4: Resource availability skyrockets with people

Up ‘til now everything has been about the negative side of scaling. Everything becomes more complex and that is going to be a headache to sort out.

But the very reason for this complexity is also the biggest boon to your project; remember, people can do more together. More people means:

more networks to tap into

more ways to reach people

more options for doing things

more capacity for change

more knowledge to draw on

In a study on social scaling by the Wallace Foundation, successful programs often compensated for increases in intervention complexity by piggy-backing on existing distribution networks, rather than beef-up their original delivery pathway.

Drawing on the collective wisdom of your population will have been one of the things you did early on in the pilot, but now co-design becomes more critical (and easier) than ever. A hundred heads are better than ten if you want to understand what’s really going on with all this complexity you’re grappling with, which is why talking to stakeholders throughout is a common recommendation in scaling.

Insight 5: Monitoring and coordination complexity increases with place and space

The flip side of gaining more social resources comes in trying to get them to work together. Coordinating any number of stakeholders and delivery channels is going to be harder. Focusing on a common goal can help with stakeholders, and fortunately monitoring and coordination do not increase as drastically with space.

Insight 6: Research and development is the key to survival

You know complexity is coming, but what form will it take? How do you know what you’re doing now will still be relevant after this rule change or that criteria tightening? Many social projects, such as poverty alleviation, will ideally try and design themselves out over time, so how do you do that rather than get bigger and bigger into a unwieldy goodness blob that is close to collapse? (I’m looking at you, NHS).

R&D is often overlooked but it’s the only way you can keep adapting to an ever changing environment. Just make sure you have the flexibility to deal with its recommendations.

This can be a tricky area to get support for if your project or organisation is mainly involved in fire fighting.

I’ve worked in several mental health services over the years, and each one had a waiting list problem (ranging from three months to the current front runner of two years). Every so often a service would hire temps at an extortionate rate to temporarily increase capacity and clear the list. They would go on as long as the budget held out, then spend the next months and years putting in requests for another emergency fund. All the while the local population gets bigger and more people come into the service, swelling the waiting list once again.

Eventually the system must collapse.

This is an example of failing complexity accommodation and it’s easy to see how it happens. Advocating for anything other than putting out fires is challenging, especially if it means a radical change in strategy.

Clearly demonstrating the logical conclusion of the current course combined with specific action to avoid it can help your case.

Insight 7: Governance cannot match increases in complexity

At the top of Beer’s model (although he stresses it’s non-hierarchical, but try telling that to the Board) sits governance and policy, which focuses on the identity of the system and why you’re doing what you’re doing.

The big problem here is that they are wrong. Always.

Identity is such a nuanced concept that yours isn’t the same across two days let alone two people. I might say you are reading this because you are interested in scaling social interventions, which has a fair chance of being true, but you might also be reading this because you’re putting off other work. Or this is how you relax. Or you’re studying linguistic devices in personal publications. Maybe all four.

The point being any single statement of identity will be at least incomplete for most people most of the time. It just cannot match the complexity.

People within any given system will have a certain amount of give to deal with this (they must be flexible after all in order to accommodate their own multi-faceted and fluctuating identity), but the more people you have the less relevant your system is overall.

Take modern country-based government. Some common descriptions include ‘out of touch’ ‘irrelevant’ and ‘betrayed the people’. This rhetoric hasn’t changed in centuries, and every so often their is a revolution to put it right. Then another one. No one government can accurately reflect the values of millions of people.

So what to do?

Devolution is a solution - one which we see played out across the world right now. The United Kingdom breaks away from the European Union, while Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland take back more control from the United Kingdom (and England devolves by default). Some in Catalonia seek independence from Spain, and in Brittany from France. State governments devolve into local governments, and on and on.

Serving smaller populations increases the relevance of the system’s identity.

Attenuation is the other solution, whereby you treat all as one and serve that assumption as well as you can. McDonald’s does this more or less benevolently; China does this less so.

So prepare for your project to one day pack up and leave the family home, seeking to make change its own way and without you.

One final point

Back in mists of time when you could happily muddle through problems thrown up by the pilot with good results, things seemed simpler. And they were. Less complex even. But that same reactivity and flexibility you used to get great results the first time round are the same qualities that are needed to continue building value at scale, rather than watching it slowly diminish.

Build a scalable system like Beer’s with enough capacity to change as you grow and you will create true scale; and not a linear assumption in sight.